Mercy in the Ditch

It starts with a test.

A lawyer—a learned man, sharp and strategic—stands up to challenge Jesus. His question sounds spiritual: “What must I do to inherit eternal life?” But the text tips us off—this isn’t longing. It’s calculation. He’s trying to trap Jesus. To get him to say too much—or the wrong thing.

Jesus doesn’t take the bait. He responds with a question of his own, pointing the lawyer back to the Law: “What’s written there?”

The lawyer answers well: “Love the Lord your God with all your heart… and your neighbor as yourself.”

Jesus nods. “Do this, and you will live.”

But the lawyer presses on. He wants to know where the limits are: “And who is my neighbor?”

That’s the question that cracks open the parable.

Jesus doesn’t define neighbor. He tells a story.

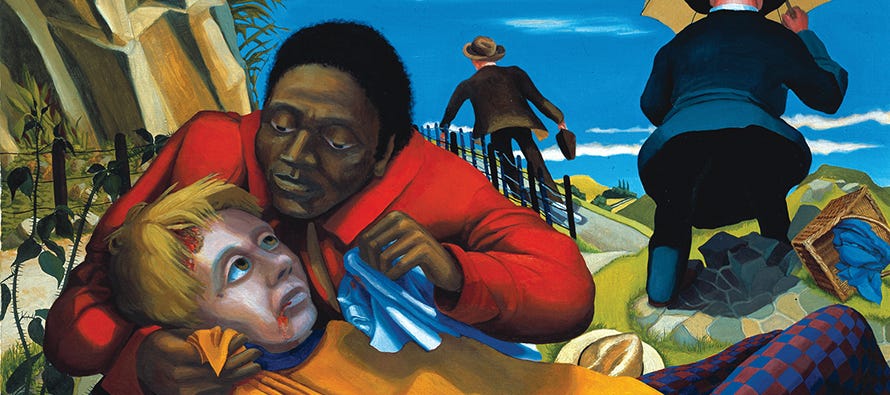

A man lies beaten by the side of the road. Three travelers pass by. The first two—a priest and a Levite—see him and cross to the other side. Religious men. Men with status. Men with reasons.

They saw… and they passed by.

Then comes a Samaritan.

Not a neutral third figure. A Samaritan—despised, distrusted, religiously suspect. The kind of person the lawyer would never name as righteous.

He sees the man. And instead of walking away, he is moved with pity.

He bandages the wounds. He lifts the body. He gives his time, his oil, his money, his care.

And then Jesus asks—not “who is your neighbor?”—but “which of these was a neighbor to the man?”

The lawyer can’t even say “the Samaritan.”

He chokes out, “the one who showed him mercy.”

It’s a brilliant reversal. The lawyer began by asking who counted as a neighbor—how far his love had to stretch. But Jesus reframes the whole thing.

It’s not about who’s in or out. It’s about how you live. How you love.

Not who is your neighbor, but how can you be one?

And the one who fulfills the Law isn’t the insider—it’s the outsider. Not the priest. Not the Levite. But the one the lawyer couldn’t bring himself to name.

That hits close to home.

Just one chapter earlier, Jesus had rebuked his disciples for wanting to call down fire on a Samaritan village. Now, a Samaritan is the hero.

Mercy—not condemnation—is what Jesus lifts up.

And the more you sit with this parable, the deeper it gets. It’s not just about kindness. It’s about who we exclude. It’s about racial and religious hostility. About love that crosses boundaries.

It’s about enemies. And grace.

And it’s about what it means to live in a world where the need feels endless.

Because that lawyer’s question—“Who is my neighbor?”—is still ours.

We ask it every time we walk down the street and make those quiet, quick decisions about who deserves our time, our attention, our care.

If you live in a city like New York, you know the feeling. Every day, you pass people lying on the side of the road. The faces change, but the ache is the same.

We see suffering—and the truth is—we can’t help everyone.

We know that. We feel that.

Sometimes we stop. Sometimes we pass by.

But Jesus doesn’t ask us to fix it all.

He asks us not to go numb. Not to give in to indifference—the place I most want to retreat when the need feels too much.

He doesn’t condemn caution. But he does challenge apathy.

For the ledger isn’t balanced.

There’s more neglect than compassion. More looking away than stepping in. Too much indifference in the debit column—and not nearly enough mercy in the credit.1

So when Jesus says, “Go and do likewise,” he’s not saying, “save the world.”

He’s inviting us to shift the weight. To tip the scales—just a little—toward mercy.

Because when we let ourselves be moved by someone else’s pain…

When we are willing to be interrupted…

When we see, and stop, and care—

We aren’t just helping someone else.

We are stepping into the life God made us for—

the life Christ died to give.

A life shaped by love.

A life of mercy.

A life that lasts.

And if we hesitate—and many of us do—

If our love falters at the lines of race or class or politics…

If our instincts are shaped more by fear than by compassion…

Then we need to remember where we were when Christ found us.

Because we were the ones in the ditch.

And sometimes the ones who cross the road to help us come from the last place we expect.

Like the woman who stepped out of the Park Slope Food Co-op, wearing a shirt with a bold progressive slogan. She tripped and fell hard on the sidewalk.

A few people glanced over. Some hesitated. Most kept walking.

Then someone stepped forward.

A man in a red cap with white lettering—the kind that usually signals a very different worldview—knelt beside her.

He steadied her. Offered water from his bag. Waited until she was okay.

He didn’t ask what she believed. He just saw someone hurting—and helped.2

It was a moment that defied expectation. That unsettles our categories—just as Jesus’ parable unsettled the lawyer’s.

And it mirrored the heart of the gospel.

Because while we were busy drawing lines—deciding who was worth our time, or trust, or love—Christ crossed the road to reach us.

Others may have passed us by.

But he did not.

He came near. He poured out mercy. He lifted us up.

He was the Good Samaritan to us.

He didn’t stop to ask if we deserved it.

He didn’t calculate the cost.

He simply saw us lying there—and was moved with compassion.

And that mercy—that undeserved, unearned grace—is what brought us back to life.

And because he has been a neighbor to us, we are now free—freer than we know—to be neighbors in return.

Not by force.

Not by guilt.

But by grace.

Because we were shown mercy.

And now, by the power of the Spirit, that mercy moves through us.

Think of these midweek reflections as a preview of what’s coming on Sunday—not the sermon itself, but a glimpse of where we’re headed. I’ll share the full sermon here after it’s preached.

Arland J. Hultgren, “Texts in Context Enlarging the Neighborhood: The Parable of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:25–37),” Word & World, Volume 37, Number 1, Winter 2017.

If I were serving a politically conservative church, I’d flip the illustration.